While Modi has celebrated India’s rapid rise in the Doing Business rankings, the World Bank’s Chief Economist recently resigned amid controversy over methodological changes. Without those changes, India’s “jump” in the rankings looks much more modest.

Download the data and replication code here.

Speaking to the assembled billionaires at Davos last month, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced triumphantly that “the largest democracy on earth is also the fastest growing major economy.” Modi used the platform to advertise that “India is open for business” and tout his accomplishments as an economic reformer—and that claim seems to have the backing of international financial institutions.

Last October, the World Bank announced that “India Jumps Doing Business Rankings with Sustained Reform Focus” moving from 130th to 100th overall. (Note the focus on the jump, or change.) The Indian press and pundits declared that the Bank had “endorsed Modi’s reform credentials.” Modi himself turned the change in Doing Business rankings into a talking political sales pitch.

Rehashing the recent Doing Business debacle

On January 12, the World Bank’s chief economist at the time, Paul Romer, told the Wall Street Journal he had lost faith in the integrity of the Doing Business index, suggesting it was being politically manipulated—particularly to embarrass Chile’s socialist president Michelle Bachelet. After a public rebuke from the World Bank CEO, Romer retracted the remarks, and then on Wednesday announced his resignation.

But as we showed in our “chart of the week”a few weeks back, the pattern Romer had uncovered speaks for itself. And Chile wasn’t the only country affected. The methodology changes pushed dozens of countries up and down as well—which bring us back to India’s recent performance on the index.

How did India perform if we ignore the questionable methodological changes?

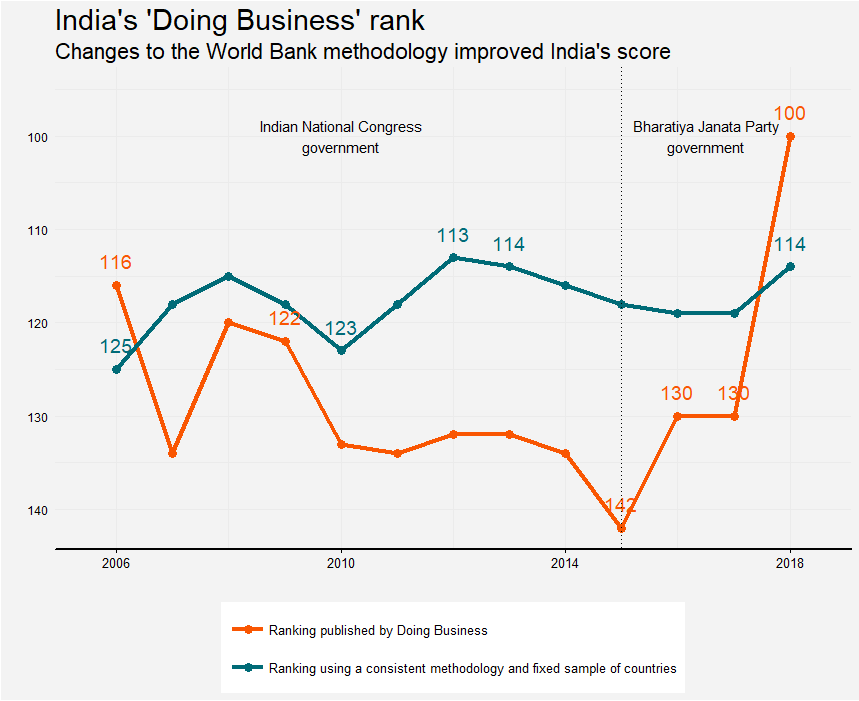

Somewhat awkwardly for the World Bank, India’s celebrated rise in the Doing Business rankings turns out to be mostly an artefact of methodological changes.

A few weeks ago we presented new data and analysis that reproduced the Doing Business rankings, dropping all of the new indicators that had been added over time, and only reporting changes for a fixed sample of countries. In an index with a more consistent methodology, Chile’s rise and fall disappears, and—if you scroll down to the bottom of last week’s post—so does the “Modi bounce.”

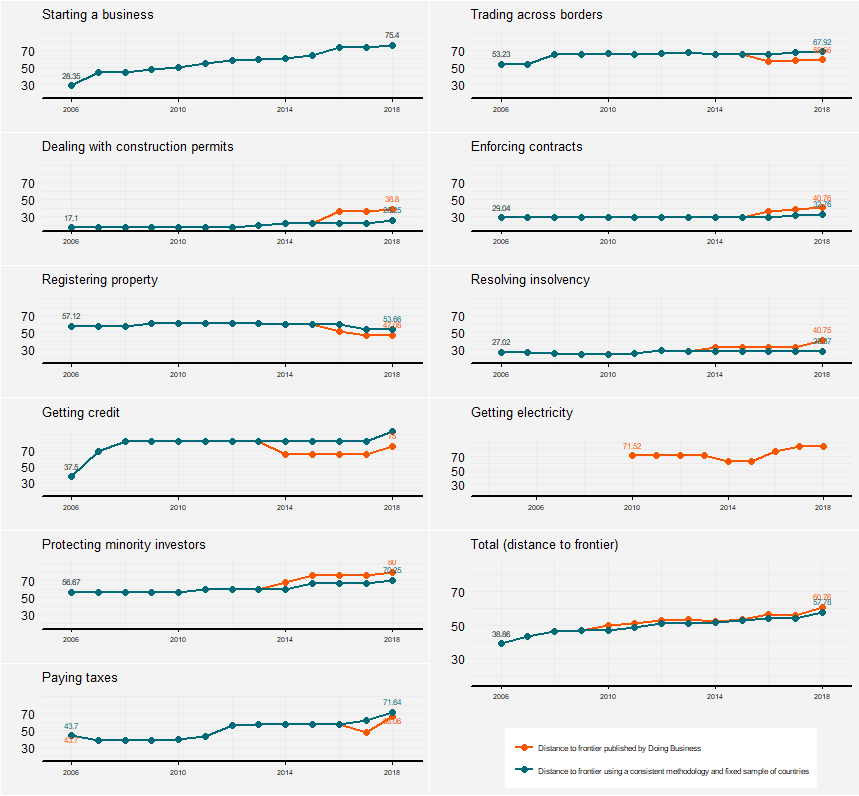

One comment we heard was that our “corrected” index was too narrow, ignoring the new and sometimes valuable features Doing Business has added. So to overcome that, we’ve gone back and tried a second approach, with much the same results for India: no recent spike in the rankings.

This time we use all the indicators available for a given year, relying on the World Bank’s own scores for each country and each component. Instead of dropping new indicators, we splice the series together whenever there is a methodological innovation. So for instance, when the World Bank changed the underlying indicators in the “ease of getting credit” index in 2014, they kindly reported the score using both methodologies for that year. India scored 81.25 on the old methodology in 2014 and 65 using the new method. Our approach is simply to multiply all of India’s credit scores by 1.25 (=81.25/65) for every year after 2014, so there is no artificial jump in India’s credit score.

The chart above has been updated to correct a mistake spotted by a reader, Vinayak Garg, who helpfully downloaded our data and code to reproduce the graph. The text of the post remains unchanged by this correction. Click here to see a side-by-side comparison of the corrected version and the original graph, which inadvertently omitted some sub-components from the index. The main point stands: the official Doing Business rankings show India rising 30 places in 2018, where as we previously found India rose only 7 places. After correcting our coding error we find India rose only 5 places, but from a higher starting point under both Congress and BJP governments.

Whichever method we use, once you iron out the methodological changes, India’s recent jump in the Doing Business rankings looks much more modest. To its credit, the World Bank office in Delhi cautioned against focusing on changes in the rankings when this issue reached public prominence in India. But those cautions were probably outweighed by the World Bank’s very own headlines, encouraging a misleading focus on India’s spurious “jump.”

A very misleading headline from the World Bank…

Which methodological changes explain this spurious jump? If we break the index down into its pieces (see below), we find that there was no single piece of the index that made the difference. Even the aggregate scores are not very different when comparing the official Doing Business scores and our revised series that irons out methodological changes.

The big change comes from ranking, not scoring. Because many countries perform similarly on the index, even small discrepancies in the score can produce wild swings in the rankings, which appears to have happened in India’s case—a point Martin Ravallion, former manager of the World Bank’s research department, has pointed out recently as well.

It seems that India’s rank moved up and down more due to the addition of new countries to the Doing Business sample than changes in methodology.

Even if you love the Doing Business index, you should acknowledge changes in ranking mean very little

Reasonable people disagree about the usefulness of the index. Critics point to serious conceptual flaws, like measuring the costs of regulation while ignoring the benefits, and how poorly the index predicts actual conditions as reported in business surveys. Defenders note that the index has spurred many countries to accelerate regulatory reforms which, they contend, has boosted growth. This debate won’t be settled anytime soon.

Reasonable people should all agree, however, with one simple fact: changes over time in the Doing Business rankings are not particularly meaningful. They largely reflect changes in methodology and sample—which the World Bank makes every year, without correcting earlier numbers—not changes in reality on the ground.

It is probably coincidence, rather than a nefarious neoliberal plot hatched in Washington, that these changes helped a right-leaning government in India and hurt a left-leaning government in Chile. But you don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to think the World Bank has been irresponsible in posting headlines about “jumps” in the Doing Business rankings, when it knew these numbers weren’t comparable over time. If it isn’t scrapped altogether, serious reform of the methodology and governance of the Doing Business index are needed