A Change in World Bank Methodology (Not Reform) Explains India’s Rise in Doing Business Rankings

While Modi has celebrated India’s rapid rise in the Doing Business rankings, the World Bank’s Chief Economist recently resigned amid controversy over methodological changes. Without those changes, India’s “jump” in the rankings looks much more modest.

Download the data and replication code here.

Speaking to the assembled billionaires at Davos last month, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced triumphantly that “the largest democracy on earth is also the fastest growing major economy.” Modi used the platform to advertise that “India is open for business” and tout his accomplishments as an economic reformer—and that claim seems to have the backing of international financial institutions.

Last October, the World Bank announced that “India Jumps Doing Business Rankings with Sustained Reform Focus” moving from 130th to 100th overall. (Note the focus on the jump, or change.) The Indian press and pundits declared that the Bank had “endorsed Modi’s reform credentials.” Modi himself turned the change in Doing Business rankings into a talking political sales pitch.

Historic jump in ‘Ease of Doing Business’ rankings is the outcome of the all-round & multi-sectoral reform push of Team India.

Rehashing the recent Doing Business debacle

On January 12, the World Bank’s chief economist at the time, Paul Romer, told the Wall Street Journal he had lost faith in the integrity of the Doing Business index, suggesting it was being politically manipulated—particularly to embarrass Chile’s socialist president Michelle Bachelet. After a public rebuke from the World Bank CEO, Romer retracted the remarks, and then on Wednesday announced his resignation.

But as we showed in our “chart of the week”a few weeks back, the pattern Romer had uncovered speaks for itself. And Chile wasn’t the only country affected. The methodology changes pushed dozens of countries up and down as well—which bring us back to India’s recent performance on the index.

How did India perform if we ignore the questionable methodological changes?

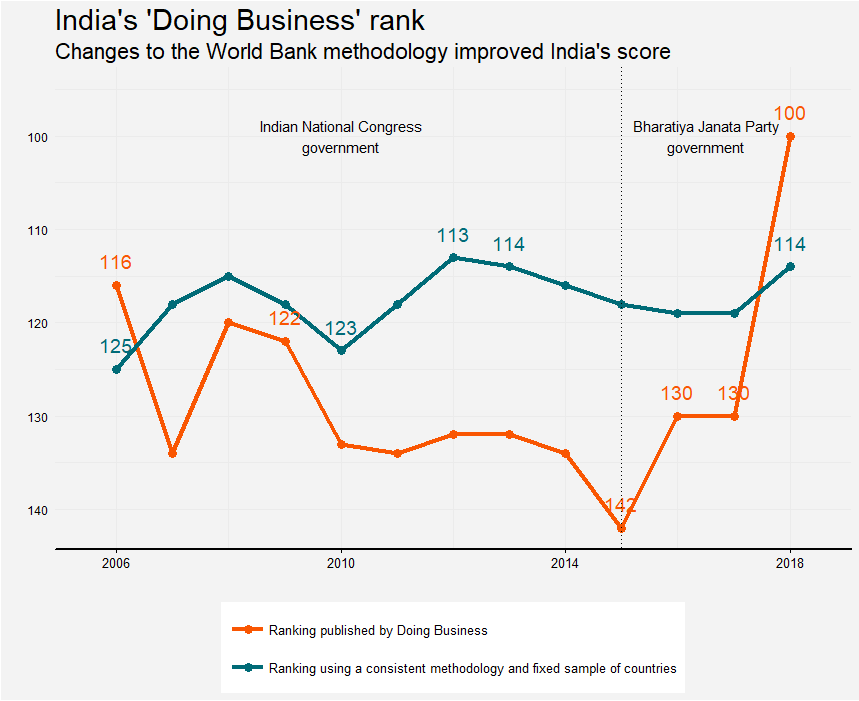

Somewhat awkwardly for the World Bank, India’s celebrated rise in the Doing Business rankings turns out to be mostly an artefact of methodological changes.

A few weeks ago we presented new data and analysis that reproduced the Doing Business rankings, dropping all of the new indicators that had been added over time, and only reporting changes for a fixed sample of countries. In an index with a more consistent methodology, Chile’s rise and fall disappears, and—if you scroll down to the bottom of last week’s post—so does the “Modi bounce.”

One comment we heard was that our “corrected” index was too narrow, ignoring the new and sometimes valuable features Doing Business has added. So to overcome that, we’ve gone back and tried a second approach, with much the same results for India: no recent spike in the rankings.

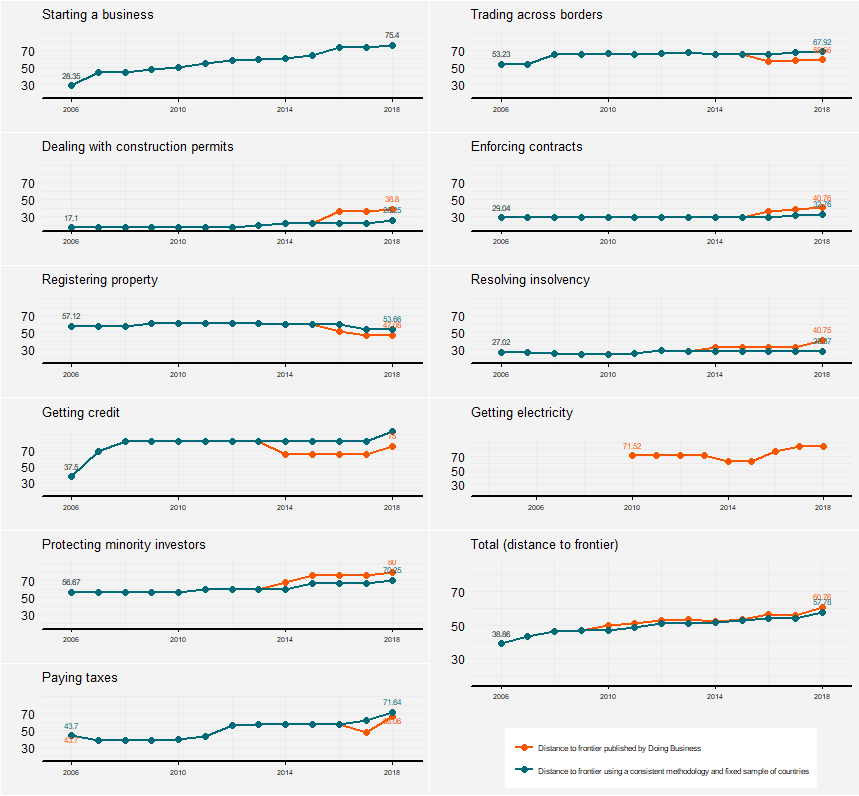

This time we use all the indicators available for a given year, relying on the World Bank’s own scores for each country and each component. Instead of dropping new indicators, we splice the series together whenever there is a methodological innovation. So for instance, when the World Bank changed the underlying indicators in the “ease of getting credit” index in 2014, they kindly reported the score using both methodologies for that year. India scored 81.25 on the old methodology in 2014 and 65 using the new method. Our approach is simply to multiply all of India’s credit scores by 1.25 (=81.25/65) for every year after 2014, so there is no artificial jump in India’s credit score.

The chart above has been updated to correct a mistake spotted by a reader, Vinayak Garg, who helpfully downloaded our data and code to reproduce the graph. The text of the post remains unchanged by this correction. Click here to see a side-by-side comparison of the corrected version and the original graph, which inadvertently omitted some sub-components from the index. The main point stands: the official Doing Business rankings show India rising 30 places in 2018, where as we previously found India rose only 7 places. After correcting our coding error we find India rose only 5 places, but from a higher starting point under both Congress and BJP governments.

Whichever method we use, once you iron out the methodological changes, India’s recent jump in the Doing Business rankings looks much more modest. To its credit, the World Bank office in Delhi cautioned against focusing on changes in the rankings when this issue reached public prominence in India. But those cautions were probably outweighed by the World Bank’s very own headlines, encouraging a misleading focus on India’s spurious “jump.”

A very misleading headline from the World Bank…

Which methodological changes explain this spurious jump? If we break the index down into its pieces (see below), we find that there was no single piece of the index that made the difference. Even the aggregate scores are not very different when comparing the official Doing Business scores and our revised series that irons out methodological changes.

The big change comes from ranking, not scoring. Because many countries perform similarly on the index, even small discrepancies in the score can produce wild swings in the rankings, which appears to have happened in India’s case—a point Martin Ravallion, former manager of the World Bank’s research department, has pointed out recently as well.

It seems that India’s rank moved up and down more due to the addition of new countries to the Doing Business sample than changes in methodology.

Even if you love the Doing Business index, you should acknowledge changes in ranking mean very little

Reasonable people disagree about the usefulness of the index. Critics point to serious conceptual flaws, like measuring the costs of regulation while ignoring the benefits, and how poorly the index predicts actual conditions as reported in business surveys. Defenders note that the index has spurred many countries to accelerate regulatory reforms which, they contend, has boosted growth. This debate won’t be settled anytime soon.

Reasonable people should all agree, however, with one simple fact: changes over time in the Doing Business rankings are not particularly meaningful. They largely reflect changes in methodology and sample—which the World Bank makes every year, without correcting earlier numbers—not changes in reality on the ground.

It is probably coincidence, rather than a nefarious neoliberal plot hatched in Washington, that these changes helped a right-leaning government in India and hurt a left-leaning government in Chile. But you don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to think the World Bank has been irresponsible in posting headlines about “jumps” in the Doing Business rankings, when it knew these numbers weren’t comparable over time. If it isn’t scrapped altogether, serious reform of the methodology and governance of the Doing Business index are needed

The World Bank Needs to Return to Its Mission

With a clear plan, the World Bank would be able to find partners to help it support progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, which has been disappointing so far. Instead, the Bank is adopting an approach that would leave poor countries mired in debt, by relying on Wall Street to finance their basic needs.

NEW YORK – The World Bank declares that its mission is to end extreme poverty within a generation and to boost shared prosperity. These goals are universally agreed as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. But the World Bank lacks an SDG strategy, and now it is turning to Wall Street to please its political masters in Washington. The Bank’s president, Jim Yong Kim, should find a better way forward, and he can do so by revisiting one of his own great successes.

Kim and I worked closely together from 2000 to 2005, to scale up the world’s response to the AIDS epidemic. Partners in Health, the NGO led by Kim and his colleague, Harvard University’s Paul Farmer, had used antiretroviral medicines (ARVs) to treat around 1,000 impoverished HIV-infected rural residents in Haiti, and had restored them to health and hope.

I pointed out to Kim and Farmer 18 years ago that their success in Haiti could be expanded to reach millions of people at low cost and with very high social benefits. I recommended a new multilateral funding mechanism, a global fund, to fight AIDS, and a new funding effort by the United States.

In early 2001, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan launched the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, and in 2003 US President George W. Bush launched the PEPFAR program. The World Health Organization, led by the Director-General Gro Harlem Brundtland, recruited Kim to lead the WHO’s scale-up effort. Kim did a fantastic job, and his efforts provided the groundwork for bringing ARVs to millions, saving lives, livelihoods, and families.

There are four lessons of that great success. First, the private sector was an important partner, by offering patent-protected drugs at production cost. Drug companies eschewed profits in the poorest countries out of decency and for the sake of their reputations. They recognized that patent rights, if exercised to excess, would be a death warrant for millions of poor people.

Second, the effort was supported by private philanthropy, led by Bill Gates, who inspired others to contribute as well. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation backed the new Global Fund, the WHO, and the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, which I led for the WHO in 2000-2001 (and which successfully campaigned for increased donor funding to fight AIDS and other killer diseases).

Third, the funding to fight AIDS took the form of outright grants, not Wall Street loans. Fighting AIDS in poor countries was not viewed as a revenue-generating investment needing fancy financial engineering. It was regarded as a vital public good that required philanthropists and high-income countries to fund life-saving treatment for poor and dying people.

Fourth, trained public health specialists led the entire effort, with Kim and Farmer serving as models of professionalism and rectitude. The Global Fund does not stuff the pockets of corrupt ministers, or trade funding for oil concessions or arms deals. The Global Fund applies rigorous, technical standards of public health, and holds recipient countries accountable – including through transparency and co-financing requirements – for delivering services.

The World Bank needs to return to its mission. The SDGs call for, among other things, ending extreme poverty and hunger, instituting universal health coverage, and universal primary and upper secondary education by 2030. But, despite making only slow progress toward these goals, the Bank shows no alarm or strategy to help get the SDGs on track for 2030. On the contrary, rather than embrace the SDGs, the Bank is practically mute, and its officials have even been heard to mutter negatively about them in the corridors of power.

Perhaps US President Donald Trump doesn’t want to hear about his government’s responsibilities vis-à-vis the SDGs. But it is Kim’s job to remind him and the US Congress of those obligations – and that it was a Republican president, George W. Bush who creatively and successfully pursued the battle against AIDS.

Wall Street may help to structure the financing of large-scale renewable energy projects, public transport, highways, and other infrastructure that can pay its way with tolls and user fees. A World Bank-Wall Street partnership could help to ensure that such projects are environmentally sound and fair to the affected communities. That would be all for the good.

Yet such projects, designed for profit or at least direct cost recovery, are not even remotely sufficient to end extreme poverty. Poor countries need grants, not loans, for basic needs like health and education. Kim should draw on his experience as the global health champion who successfully battled against AIDS, rather than embracing an approach that would only bury poor countries in debt. We need the World Bank’s voice and strenuous efforts to mobilize grant financing for the SDGs.

Health care for the poor requires systematic training and deployment of community health workers, diagnostics, medicines, and information systems. Education for the poor requires trained teachers, safe and modern classrooms, and connectivity to other schools and to online curricula. These SDGs can be achieved, but only if there is a clear strategy, grant financing, and clear delivery mechanisms. The World Bank should develop the expertise to help donors and recipient governments make these programs work. Kim knows just how to do this, from his own experience.

Trump and other world leaders are personally accountable for the SDGs. They need to do vastly more. So, too, do the world’s super-rich, whose degree of wealth is historically unprecedented. The super-rich have received round after round of tax cuts and special tax breaks, easy credits from central banks, and exceptional gains from technologies that are boosting profits while lowering unskilled workers’ wages. Even with stock markets’ recent softness, the world’s 2000+ billionaires have around $10 trillion in wealth – enough to fund fully the incremental effort needed to end extreme poverty, if the governments also do their part.

When going to Wall Street, or Davos, or other centers of wealth, the World Bank should inspire the billionaires to put their surging wealth into personal philanthropy to support the SDGs. Bill Gates is doing this, with historic results, for public health. Which billionaires will champion the SDGs for education, renewable energy, fresh water and sanitation, and sustainable agriculture? With a clear SDG plan, the World Bank would find partners to help it fulfill its core, historic, and vital mission.

Read more

Cryptocurrencies Are Like Ponzi Schemes, World Bank Chief Says

The head of the World Bank compared cryptocurrencies to “Ponzi schemes,” the latest financial voice to raise questions about the legitimacy of digital currencies such as Bitcoin.

“In terms of using Bitcoin or some of the cryptocurrencies, we are also looking at it, but I’m told the vast majority of cryptocurrencies are basically Ponzi schemes,” World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim said Wednesday at an event in Washington. “It’s still not really clear how it’s going to work.”

The development lender is “looking really carefully” at blockchain technology, a platform that uses so-called distributed ledgers to allow digital assets to be traded securely. There’s hope the technology could be used in developing countries to “follow the money more effectively” and reduce corruption, Kim said.

The value of cryptocurrencies soared in 2017 before slumping, with Bitcoin losing nearly two-thirds of its value since mid-December.

While cryptocurrency technology has the potential to reshape global finance, concerns have been raised about its volatility and the potential for money laundering or other crimes.

Nouriel Roubini Says Bitcoin 'Much Worse' Than Tulip Mania

Nouriel Roubini discusses the downsides to cryptocurrencies and calls Bitcoin the "mother of all bubbles."

(Source: Bloomberg)

In a speech this week, Bank of International Settlements chief Agustin Carstens said there’s a “strong case” for authorities to rein in digital currencies because their links to the established financial system could cause disruptions. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has said that “governance and risk management will be critical” for cryptocurrencies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)