Showing posts with label Protectionism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Protectionism. Show all posts

Protectionism

BACK in 1906, an

insurgent politician called Joseph Chamberlain (once known as Radical

Joe, he had switched to the Conservatives over home rule for Ireland*)

lured the government into a campaign in favour of tariffs. The result

was a devastating defeat for the Conservatives. The opposition Liberal

party recognised that tariffs were a tax on the goods bought by the

poor, particularly on food, and warned that the policy would lead to a

"smaller loaf". They portrayed tariffs as "stomach taxes".

A hundred years ago, then, it was easy to make protectionism unpopular. Despite the prosperity brought by 70 years under a more open trading system, it now seems that opinion may have changed: tariffs are favoured by "populist" politicians.**

The trick for modern populists has been to focus on the positive benefits to American workers in terms of jobs, rather than the adverse impact on consumers. In fact, protectionism is highly unlikely to restore American manufacturing jobs, which are under threat from automation as well as globalisation, as our recent briefing showed.

That is partly because in a world of low tariffs, consumers have become pretty blasé about buying goods from all over the world. "You don't know what you've got until you lose it" as John Lennon sang. Even the small level of existing tariffs fall most heavily on the poor, academics reckon, reducing the after-tax income of the poorest by 1.6% and that of the richest by only 0.3%.

This means the anti-tariff campaign will have to campaign hard to show the harm tariffs do to consumers. America is a net exporter of food, so it is hard to use the images that worked so well 100 years ago. Still, it is in the nature of modern trade that developed countries sell high-added-value goods and services (like software) and import raw materials and low value added goods from developing countries (cheap clothing, for example). A study in May by the National Foundation for American Policy found that

* He was wrong about that too. If home rule had been granted in the late 19th century, a lot of bloodshed might have been avoided.

** Admittedly this category is ill-defined. In my view populism defines policies that may seem popular but would have negative effects, either on individual rights or (often) on the very people that support them.

Source....

A hundred years ago, then, it was easy to make protectionism unpopular. Despite the prosperity brought by 70 years under a more open trading system, it now seems that opinion may have changed: tariffs are favoured by "populist" politicians.**

The trick for modern populists has been to focus on the positive benefits to American workers in terms of jobs, rather than the adverse impact on consumers. In fact, protectionism is highly unlikely to restore American manufacturing jobs, which are under threat from automation as well as globalisation, as our recent briefing showed.

That is partly because in a world of low tariffs, consumers have become pretty blasé about buying goods from all over the world. "You don't know what you've got until you lose it" as John Lennon sang. Even the small level of existing tariffs fall most heavily on the poor, academics reckon, reducing the after-tax income of the poorest by 1.6% and that of the richest by only 0.3%.

This means the anti-tariff campaign will have to campaign hard to show the harm tariffs do to consumers. America is a net exporter of food, so it is hard to use the images that worked so well 100 years ago. Still, it is in the nature of modern trade that developed countries sell high-added-value goods and services (like software) and import raw materials and low value added goods from developing countries (cheap clothing, for example). A study in May by the National Foundation for American Policy found that

Presidential candidate Donald Trump’s proposed tariffs on China, Mexico and, by implication, Japan would be ineffective in shielding American workers from foreign imports, since producers from other countries would export the same products to the United States. Were such tariffs to be “effective,” then the tariffs would impose a regressive consumption tax of $11,100 over 5 years on the typical U.S. household. The impact would hit poor Americans the hardest: A tariff of 45% on imports from China and Japan and 35% on Mexican imports would cost US households in the lowest 10% of income up to 18% of their (mean) after-tax income or $4,670 over 5 years.But what if the United States imposed a worldwide tariff, rather than singling out specific countries? The effects would be even worse.

When we calculate the burden as a percentage of household income, we find that households in the lower income deciles would surrender a higher portion of their income under a Trump tariff than higher income households. A Trump tariff against all countries costs households in the lowest decile 53% of their annual income, while it would cost households in the highest decile 7% of their incomes. The tariffs would cost households in the second income decile 20% of their annual income—a figure that declines as we move up the income deciles. In other words, a Trump tariff against all countries (or even one against only China, Mexico and Japan) would be a regressive tax that burdens lower income households more than higher income households.Combine this with a set of tax cuts that will benefit the rich most and it seems clear that this aspect of populism ought not to be popular at all. Introducing tariffs may not mean a smaller loaf but it will mean that Americans lose their shirts.

* He was wrong about that too. If home rule had been granted in the late 19th century, a lot of bloodshed might have been avoided.

** Admittedly this category is ill-defined. In my view populism defines policies that may seem popular but would have negative effects, either on individual rights or (often) on the very people that support them.

Source....

Is Free Trade Good or Bad?

Free trade is something of a sacred cow in the economics profession.

Moving towards it, rather slowly, has also been one of the dominant features of the post-World War Two global economy. Now there are new challenges to that development.

The UK is leaving the European Union and the single market - though in her speech this week, British Prime Minister Theresa May promised to push for the "freest possible trade" with European countries and to sign new deals with others around the world.

Most obviously Donald Trump has raised the possibility of quitting various trade agreements, notably Nafta, the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico and Canada. Even the World Trade Organization (WTO) has proposed new barriers to imports.

In Europe, trade negotiations with the United States and Canada have run into difficulty, reflecting public concerns about the impact on jobs, the environment and consumer protection.

The WTO's Doha Round of global trade liberalisation talks has run aground.

The case for trade without government imposed barriers has a long history in economics.

Comparative advantage

Adam Smith, the 18th Century Scottish economist who many see as the founding father of the subject, was in favour of it. But it was a later British writer, David Ricardo in the 19th Century, who set out the idea known as comparative advantage that underpins much of the argument for freer trade.It is not about countries being able to produce more cheaply or efficiently than others. You can have a comparative advantage in making something even if you are less efficient than your trade partner.

When a country shifts resources to produce more of one good there is what economists call an "opportunity cost" in terms of how much less of something else you can make. You have a comparative advantage in making a product if the cost in that sense is less than it is in another country.

If two countries trade on this basis, concentrating on goods where they have a comparative advantage they can both end up better off.

Another reason that economists tend to look askance at trade restrictions comes from an analysis of the impact if governments do put up barriers - in particular tariffs or taxes - on imports.

There are gains of course. The firms and workers who are protected can sell more of their goods in the home market. But consumers lose out by paying a higher price - and consumers in this case can mean businesses, if they buy the protected goods as components or raw materials.

Avoiding protectionism

The textbook analysis says that those losses add up to more than the total gains. So you get the textbook conclusion that it's best to avoid protection.And this conclusion is regardless of what other countries do. The 19th Century French economist Frederic Bastiat set it out it like this:

"It makes no more sense to be protectionist because other countries have tariffs than it would to block up our harbours because other countries have rocky coasts."

The implication is that unilateral trade liberalisation makes perfect sense.

A more recent theory of what drives international trade looks at what are called economies of scale - where the more a firm produces of some good, the lower cost of each unit.

The associated specialisation can make it beneficial for economies that are otherwise very similar to trade with one another. This area is known as new trade theory and the Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman was an important figure in developing it.

Post-war trade

The basic idea that it's good to have freer trade has underpinned decades of international co-operation on trade policy since World War Two.Read full article....

Arguments for Protectionism

Building Some Arguments for Protectionism

Fledging industry argument: Certain industries possess a

possible comparative advantage but have not yet exploited enough

economies of scale. Short-term protection allows the infant industry to

develop its advantage at which point protection could be relaxed,

leaving an industry to trade more freely on the international market.

Externalities and market failure: Protectionism can be used to internalize the social costs of de-merit goods. Or to correct for wider environmental market failures

Protection of jobs in home industries and an improvement in a country’s balance of payments

Protection of strategic industries: A government may wish to protect employment in strategic industries, although value judgments are involved in determining what constitutes a strategic sector.

Anti-dumping duties: Dumping is a type of predatory pricing behaviour and a form of price discrimination. Goods are dumped when they are sold for export at less than their normal value. The normal value is usually defined as the price for the like goods in the exporter’s home market. In the short term, consumers benefit from the lower prices of the foreign goods, but in the longer-term, persistent undercutting of domestic prices can force a domestic industry out of business and allow the foreign firm to establish itself as a monopoly. Once this is achieved the foreign owned monopoly is free to increase prices and exploit the consumer. Therefore protection, via tariffs on 'dumped' goods can be justified to prevent the long-term exploitation of the consumer.

Externalities and market failure: Protectionism can be used to internalize the social costs of de-merit goods. Or to correct for wider environmental market failures

Protection of jobs in home industries and an improvement in a country’s balance of payments

Protection of strategic industries: A government may wish to protect employment in strategic industries, although value judgments are involved in determining what constitutes a strategic sector.

Anti-dumping duties: Dumping is a type of predatory pricing behaviour and a form of price discrimination. Goods are dumped when they are sold for export at less than their normal value. The normal value is usually defined as the price for the like goods in the exporter’s home market. In the short term, consumers benefit from the lower prices of the foreign goods, but in the longer-term, persistent undercutting of domestic prices can force a domestic industry out of business and allow the foreign firm to establish itself as a monopoly. Once this is achieved the foreign owned monopoly is free to increase prices and exploit the consumer. Therefore protection, via tariffs on 'dumped' goods can be justified to prevent the long-term exploitation of the consumer.

Anti-dumping duties and the World Trade Organisation

The World Trade Organisation allows a national government to act against dumping where there is genuine ‘material’ injury to the competing domestic industry.

In order to do that the government has to be able to show that dumping is taking place, calculate the extent of dumping (how much lower the export price is compared to the exporter’s home market price), and show that the dumping is causing injury.

Usually an ‘anti-dumping action’ means charging extra import duty on the particular product from the particular exporting country in order to bring its price closer to the “normal value”.

Import tariffs are not normally a major source of tax revenue for the Government that imposes them. In the UK for example, tariffs are estimated to be worth only £2 billion to the Treasury, equivalent to only 0.5% of the total tax take. Developing countries tend to be more reliant on import tariffs for extra tax revenues.

The World Trade Organisation allows a national government to act against dumping where there is genuine ‘material’ injury to the competing domestic industry.

In order to do that the government has to be able to show that dumping is taking place, calculate the extent of dumping (how much lower the export price is compared to the exporter’s home market price), and show that the dumping is causing injury.

Usually an ‘anti-dumping action’ means charging extra import duty on the particular product from the particular exporting country in order to bring its price closer to the “normal value”.

Import tariffs are not normally a major source of tax revenue for the Government that imposes them. In the UK for example, tariffs are estimated to be worth only £2 billion to the Treasury, equivalent to only 0.5% of the total tax take. Developing countries tend to be more reliant on import tariffs for extra tax revenues.

Arguments against Protectionism

What are some of the main economic and social arguments against trade protectionist policies?

- Market distortion and loss of allocative efficiency: Protectionism can be an ineffective and costly means of sustaining jobs.

- Higher prices for consumers: Tariffs push up the prices for consumers and insulate inefficient sectors from genuine competition. They penalise foreign producers and encourage an inefficient allocation of resources both domestically and globally.

- Reduction in market access for producers: Export subsidies depress world prices and damage output, profits, investment and jobs in many lower-income developing countries that rely on exporting primary and manufactured goods for their growth.

- Loss of economic welfare: Tariffs create a deadweight loss of consumer and producer surplus. Welfare is reduced through higher prices and restricted consumer choice. The welfare effects of a quota are similar to those of a tariff – prices rise because an artificial scarcity of a product is created.

- Extra costs for exporters: For goods that are produced globally, high tariffs and other barriers on imports act as a tax on exports, damaging economies, and jobs, rather than protecting them

- Regressive effect on the distribution of income: Higher prices from tariffs hit those on lower incomes hardest, because the tariffs (e.g. on foodstuffs, tobacco, and clothing) fall on products that lower income families spend a higher share of their income.

- Production inefficiencies: Firms that are protected from competition have little incentive to reduce their production costs. This can lead to X-inefficiency and higher average costs.

- Trade wars: There is the danger that one country imposing import controls will lead to retaliatory action by another leading to a decrease in the volume of world trade. Retaliatory actions increase the costs of importing new technologies affecting LRAS. Students should mention game theory when discussing the risks of retaliation with countries embroiled in trade disputes.

- Negative multiplier effects: If one country imposes trade restrictions on another, the resultant decrease in trade will have a negative multiplier effect affecting many more countries because exports are an injection of demand into the global circular flow of income.

- Second best approach: Protectionism is a second best approach to correcting for a country's balance of payments problem or the fear of structural unemployment. Import controls go against the principles of free trade. In this sense, import controls can cause government failure.

Economic Nationalism

Economic nationalism describes policies to protect domestic consumption, jobs and investment using tariffs and other barriers to the movement of labour, goods and capital

The term gained a more specific meaning in recent years after several European Union governments intervened to prevent takeovers of domestic firms by foreign companies. In some cases, the national governments also endorsed counter-bids from compatriot companies to create 'national champions'. Such cases included the proposed takeover of Arcelor (Luxembourg) by Mittal Steel (India). And the French government listing of the food and drinks business Danone (France) as a 'strategic industry' to block potential takeover bid by PepsiCo (USA

Economic nationalism describes policies to protect domestic consumption, jobs and investment using tariffs and other barriers to the movement of labour, goods and capital

The term gained a more specific meaning in recent years after several European Union governments intervened to prevent takeovers of domestic firms by foreign companies. In some cases, the national governments also endorsed counter-bids from compatriot companies to create 'national champions'. Such cases included the proposed takeover of Arcelor (Luxembourg) by Mittal Steel (India). And the French government listing of the food and drinks business Danone (France) as a 'strategic industry' to block potential takeover bid by PepsiCo (USA

Trump's Protectionism

Protectionism represents any attempt to impose restrictions on trade in goods and services

Trade disputes between countries happen because one or

more parties either believes that trade is being conducted unfairly, on

an uneven playing field, or because they believe that there is one or

more economic or strategic justifications for import controls.

All countries operate with some forms of import controls

The aim is to cushion domestic businesses and industries from overseas competition and prevent the outcome resulting from the inter-play of free market forces of supply and demand.

Different forms of protectionism

All countries operate with some forms of import controls

The aim is to cushion domestic businesses and industries from overseas competition and prevent the outcome resulting from the inter-play of free market forces of supply and demand.

Different forms of protectionism

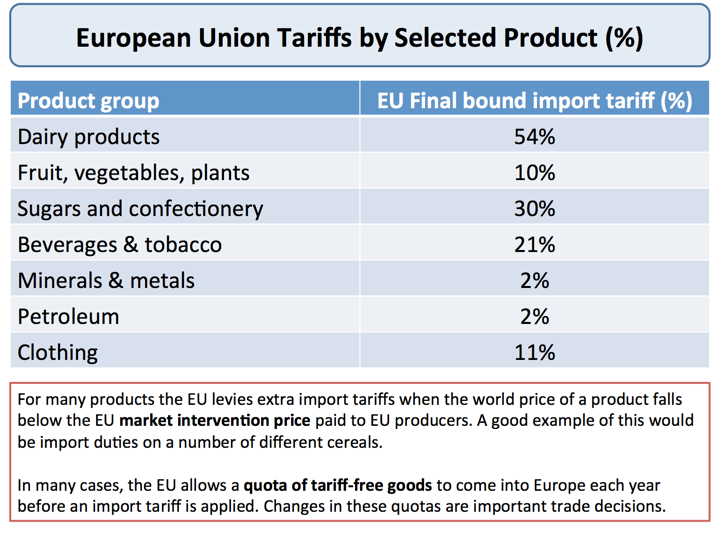

- Tariffs - a tax or duty that raises the price of imported products and causes a contraction in domestic demand and an expansion in domestic supply. For example, until recently, Mexico imposed a 150% tariff on Brazilian chicken. The United States has an 11% import tariff on imports of bicycles from the UK.

- Quotas – these are quantitative (volume) limits on the level of imports allowed or a limit to the value of imports permitted into a country in a given time period. Until 2014, South Korea maintained strict quotas on imported rice. It has now replaced an annual import quota with import tariffs designed to protect South Korean rice farmers. Quotas do not normally bring in any tax revenue for the government

- Voluntary Export Restraint – this is where two countries make an agreement to limit the volume of their exports to one another over an agreed time period. Sometimes this is enforced by a government for example the USA enforced VER on Japan during the late 1980s

- Intellectual property laws e.g. patents and copyright protection

- Technical barriers to trade including product labeling rules and stringent sanitary standards. These increase product compliance costs and impose monitoring costs on export agencies. Huge vertically integrated businesses can cope with these non-tariff barriers but many of the least developed countries do not have the some technical sophistication to overcome these barriers.

- Preferential state procurement policies – this is where a government favour local/domestic producers when finalizing contracts for state spending e.g. infrastructure projects or purchasing new defence equipment

- Export subsidies - a payment to encourage domestic production by lowering their costs. Soft loans can be used to fund the dumping of products in overseas markets. Well known subsidies include Common Agricultural Policy in the EU, or cotton subsidies for US farmers and farm subsidies introduced by countries such as Russia. In 2012, the USA government imposed tariffs of up to 4.7 per cent on Chinese manufacturers of solar panel cells, judging that they benefited from unfair export subsidies after a review that split the US solar industry.

- Domestic subsidies – government help (state aid) for domestic businesses facing financial problems e.g. subsidies for car manufacturers or loss-making airlines.

- Import licensing - governments grants importers the license to import goods.

- Exchange controls - limiting the foreign exchange that can move between countries – this is also known as capital controls

- Financial protectionism – for example when a national government instructs banks to give priority when making loans to domestic businesses

- Murky or hidden protectionism - e.g. state measures that indirectly discriminate against foreign workers, investors and traders. A government subsidy that is paid only when consumers buy locally produced goods and services would count as an example. Deliberate intervention in currency markets might also come under this category.

Examiner’s tip: the tariff is frequently examined. Ensure that you can analyse the removal as well as the imposition of a tariff.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)